#33 - More To The Story

Just A Technicality

The trigger for the investigation of the Pagami Creek Fire was that four firefighters deployed fire shelters on a small island on 12 September 2011 (on Lake Insula, in northern Minnesota). I’m not talking about Jess and Jamie’s story. I’m talking about a different event that happened nearby, at about the same time.

Early on, the shelter deployment on the island was described as “precautionary”— meaning that firefighters overreacted in an otherwise safe situation. No big deal. This was the perception among some of the local leaders. But, agency policy required every deployment to be investigated (even unnecessary ones). So our investigation was seen almost as a formality.

You may be tempted to write off those executives as dismissive, but don’t be too quick to judge. The truth is they didn’t have the whole story yet. How could they? Their assumptions were based on the information they had.

Consider, for example: the island where the deployment happened was tiny and mostly bare. You can see this island in the following photo (the lower arrow points to it). It’s hard to imagine how the fire could even reach that island, much less overrun it or pose any real danger. That was my impression as part of the investigation team when I first saw that photo.

This is a key point when it comes to accidents and close calls: first impressions are often wrong.

More To The Story

Here’s what the investigation team learned when they started interviewing people who were actually involved with the shelter deployment.

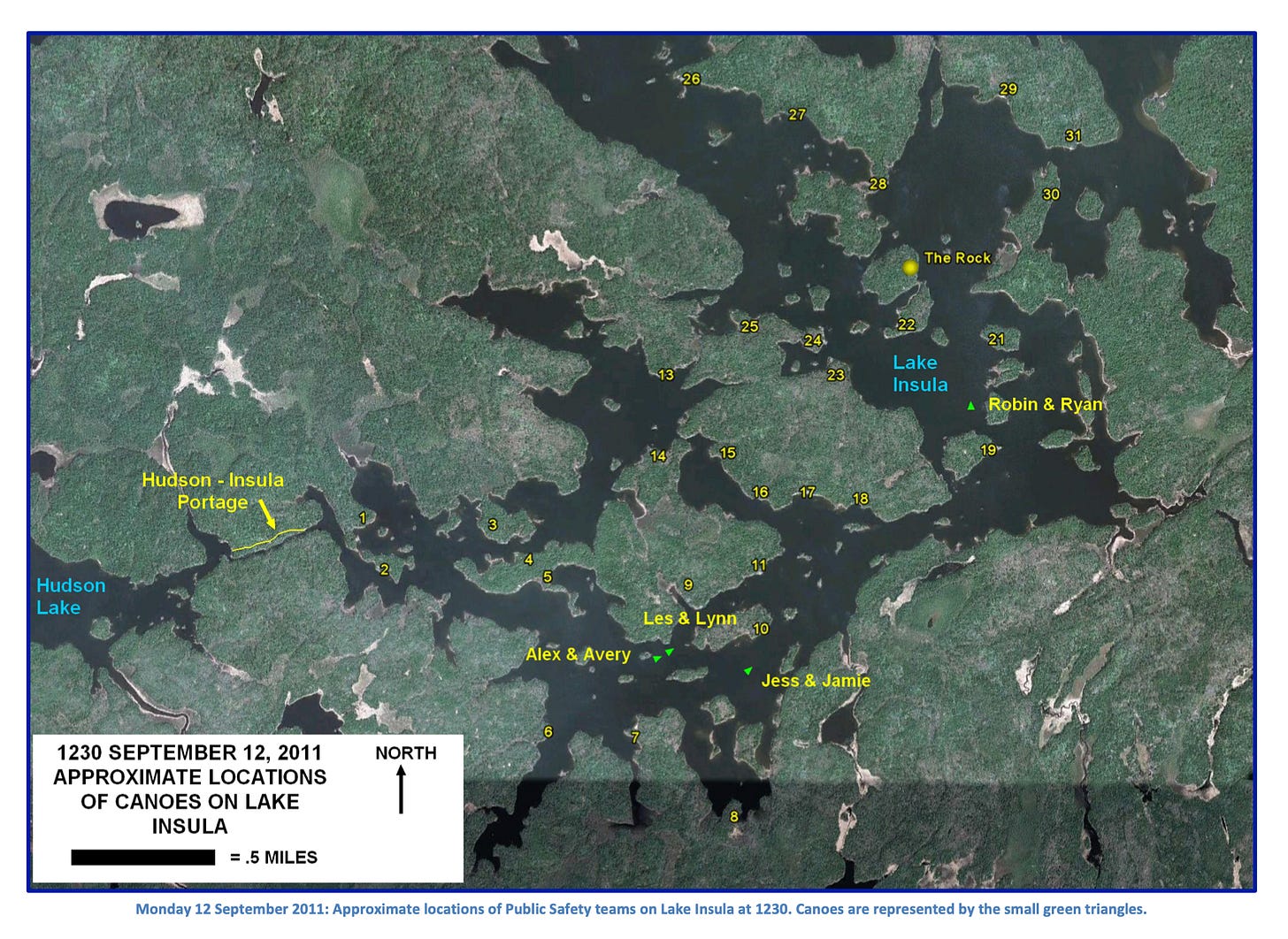

Shortly before noon on Monday, 12 September, two two-person teams met up at the portage between Lake Hudson and Lake Insula (see map below, portage is on the left). As they talked, they heard a sound in the distance to the south. They they thought it could be the fire. But that seemed doubtful -- the fire was supposed to be far from them and moving in the other direction. They realized their radios could not reach incident command from where they were. Nor could they reach aircraft over the fire to ask what was going on.

The roar in the distance grew, and they decided to make a run for it, not even taking time to break down their camp a short distance away. They loaded into their two canoes and paddled hard into Lake Insula, heading east, trying to get away from the shore. They knew the water would be their safety zone.

But they were wrong.

As the wind and waves picked up, it was a struggle to keep the canoes stable. They were getting water over the bow and came close to swamping. This would leave them stranded in the middle of the frigid lake without gear, radios, or transportation. They would be adrift with the shoreline blazing and the wind and waves tossing them around. If they were going to avoid ditching, they would need dry land. But it was all covered in timber, even the islands.

As the fire slammed the shoreline south of them, they felt waves of heat. Then smoke covered the sky, blocking out the sun. It was pitch black, to the point they actually put on headlamps. The sky filled with bats. Then it got so smoky they couldn’t see the front of their own canoes.

They kept paddling.

They turned north. And then, with the wind at their backs, they were “surfing,” one told me--he said he’d never gone that fast in a canoe. They knew the danger of course: if they hit a little reef going that fast, it would shred their canoes.

Suddenly they spotted a tiny island with no trees on it. Then it disappeared in the smoke. They paddled for it, but it came in and out of view. If they couldn’t reach the island, they were going to have to ditch and take their chances in the lake. They kept paddling and were sure they must have passed it. Then the smoke thinned and they saw the island; it was close, and they beached there. Here’s how things went from there (from the Pagami Report):

The struggle’s over.

What’s next? We’re good here; this is a safety zone. Right? It’s not gonna get too hot here. Or...how far can superheated gases travel over water? The fire’s already done things they couldn’t believe. The lake was supposed to be safe, and that didn’t work. The fire front will be even with them in five to ten minutes, they can hear the roar.

Alex says, “Okay, let’s get the fire shelters ready.” But he’s wondering if they should use them. If they do, people are going to make a big deal of it, “like, oh s### they had a DEPLOYMENT!” Avery’s shelter is already out; he’s shaking it open and crawling inside.

Alex says to just get them ready. Avery says they shouldn’t wait to deploy in 60mph winds. They pick spots to deploy, move the canoes so they aren’t directly upwind, and grab gloves, water, radios and other PPE, talking the whole time as they remember details from the shelter training video. They contact Air Attack and tell him they have a good spot.

Alex is wondering whether shelters are really necessary. The wind picks up, and with the smoke it’s pitch black again and showering “millions of firebrands covering everything.” Their eyes are burning; it’s difficult to breathe, and they are getting pelted with firebrands—they don’t know if the column is going to collapse down upon them. At 1315, Alex says, “Okay, get in.” They’re relieved once the decision is made. It’s done, and there’s nothing left to question. It’s safer inside; they can finally breathe and gather their thoughts. (Pagami Report, pp. 8,9)

As it turned out, the shelter deployment was not some minor technicality or careless precaution. It was a choice. Just one in a long series of maneuvers, trying to survive in in a highly Dynamic, Ambiguous, Risky, and Complex (DARC) environment.

But that wasn’t the whole story.

Even More To The Story

The investigation team also discovered Jess and Jamie’s close call, which happened in the water, not far from the deployment island. In the photo above, the upper red arrow shows their path of travel.

And yet, that wasn’t the whole story.

The investigation team discovered yet another close call, this one involving a floatplane and another canoe team.

Here is Robin and Ryan’s story, from the Pagami Report (they were the fourth canoe team on Lake Insula, north of the other three canoe teams we talked about):

[T]hey beach in a boggy area and find what seems like a good deployment site. Now, it’s a little after 1400. They’re on the edge of the column. The fire front spans the horizon to the south, and is heading their way. A floatplane pilot radios, “I think I can get in there and land, if you guys can get out on the water. That water’s rough, but I’ve got an opening in the smoke, so if I can find you, I can probably get in there and pick you up.” They tell the pilot they don’t think they can get away from shore because of the waves. Paddling looks less safe than staying put. Then somehow the water seems to calm a bit, and the wind shifts—now the column’s moving east and there’s a clearing in the smoke. The pilot urges them again to paddle out. “Looks safe to me.” “Let’s go.” They jump into the canoe and paddle hard for the center of the bay. The plane skims onto the water, bouncing heavily on big waves. They paddle over, kick away the canoe with their gear, and take off, planning to search for public until the pilot needs to refuel. (p. 10)

So, contrary to the first impression of many local executives and even the investigation team—Pagami was not some minor event, it was a cluster of very serious close calls, and each of them could easily have turned out very differently.

The Big Question

The investigation team’s job was to make sense of how these close calls happened. To me, the main factor was the fire behavior—it was unpredicted by the best models, and it was unprecedented. And this created all kinds of trouble, like with the radios. Because the fire spread so quickly, firefighters were forced into areas that did not have repeaters set up yet (places where you’d never need repeaters on a normal fire). Those firefighters thus lost communication and couldn’t get updates on the fire’s location. Normally, they would have been able to contact aircraft over the fire as a source of information. But aircraft were occupied elsewhere, because of a new fire that started nearby. This is an example of how the fire behavior itself caused a number of problems that compounded each other. Of course there were a number of other conditions and you can read about them in the report, but to me the unprecedented and unpredictable fire behavior was the primary factor.

The more I dug into the events of 12 September, the more I wondered how these firefighters were able to maneuver to safety and survive in such in a Dynamic, Ambiguous, Risky, and Complex (DARC) environment. The odds were against them. Time and again, they almost ran out of luck. Their margins were so narrow, and yet, somehow they all maneuvered to safety.

I realized we needed to ask a new question.

The big question was not “Why did something bad happen?” (Yes, of course we had to answer that, but that wasn’t the big question.) The big question was, “How did they survive, when the environment was so DARC?”

In other words, we needed to understand the causes of their survival, not just the causes of their trouble.

The question actually had life and death implications for other firefighters. All firefighter accidents and close calls (and successes too) happen in the DARC. If we could learn something about how firefighters survived the DARC on the Pagami Creek Fire, those insights could help other firefighters maneuver better in the in the DARC.

I dug and dug and it turns out, there was even more to the story.

Until now we’ve been talking about the events of Monday, 12 September 2011. But to really understand those stories, you need to know what happened two days before.