#37 - Communication Is The Key

Jess and Jamie

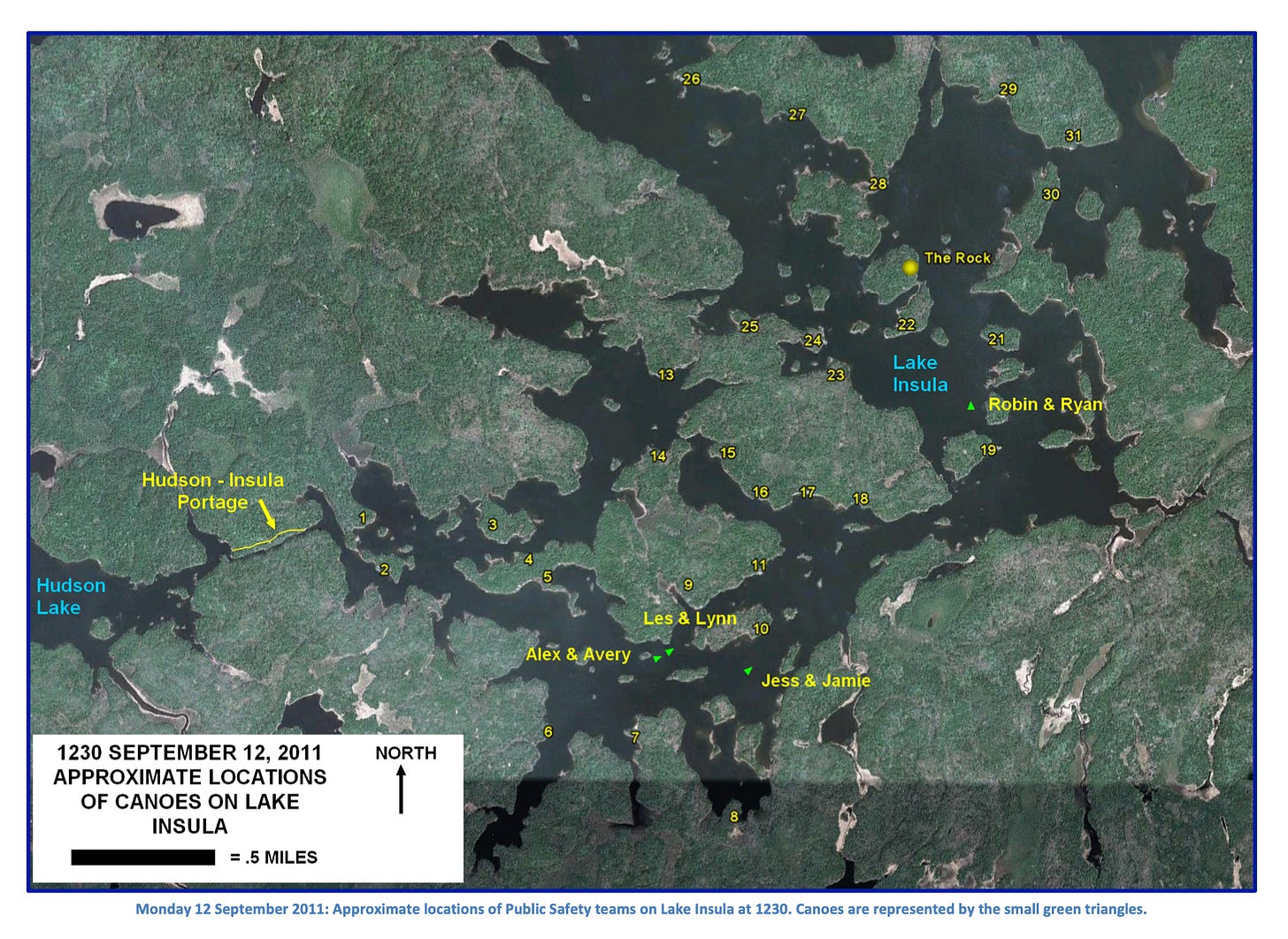

Rewind to the 0700 morning briefing 12 September 2011 (the day the fire blew up). Each morning, each canoe team working in the area would find a spot where they had good radio coverage. They’d listen to the morning briefing by radio and receive their individual assignments for the day. Jess and Jamie’s assignment was to work the southern edge of Lake Insula and advise (but not force) campers to leave the area. Jess called back and pushed against this assignment. She didn’t think the assignment made much sense, based on conditions in the field. She suggested they completely evacuate the entire southern part of the lake.

This is exactly the kind of communication leaders want. They can’t run the fire AND be out on the lakes at the same time. They make decisions based on the intel they get, and they know it’s always somewhat incomplete and outdated. That’s the nature of incident management. So when they gave Jess an assignment that seemed out of touch with operational realities, she did her job. She let the higher ups know what she was seeing on the ground, and she offered an alternative.

Perfect.

This is different from how firefighters acted on Saturday, 10 September 2011. That day, they were less assertive in their communication. They got messages from Incident Command that didn’t really make sense, and they went with the flow rather than pushing back. They saw problems in the field, but that information didn’t make it back to Incident Command. This patient approach worked fine in the area most of the time, given the low intensity of fires there. That’s why it was the norm.

So, it’s significant that Jess pushed back against the assignment, instead of doing the normal thing and going with the flow.

After she spoke up, her supervisor called back, and expanded the evacuation area—beyond even what Jess had suggested.

I asked Jess why she decided to speak up at that moment, since it was rather unusual. She told me it was because she “[thought] about the stories she heard of emergency closures late on Saturday. She [didn’t] want a repeat.” (Pagami Report, p. 10)

So, that’s clear evidence Jess made a better decision on Monday, because she learned from what happened Saturday.

The Twist

Now, here’s the twist: Jess wasn’t part of the close calls Saturday. She and Jamie weren’t even on the lakes that day. They arrived Sunday.

So how did she learn? She learned from “the stories she heard.”

And how did she hear those stories? In the normal course of her work Sunday, she crossed paths with two other teams working the lakes, and they told her about the close calls the day before.

This is the key point: Jess and Jamie didn’t have to live through Saturday’s close calls to learn from them. They learned because they talked to people who were there. That was enough to save their lives.

Just Imagine

Imagine if they hadn’t talked—if Jess and Jamie had to learn their own lessons on Monday instead of learning other people’s lessons from Saturday.

Here’s an example of a moment that could have gone differently:

Monday morning, at about 1045, they tied in with another canoe team (Robin and Ryan), who just flew in. They divided up the day’s work, and Jess told them about Saturday’s close calls.1 Then the two teams went their separate ways. Then this happened:

Soon the wind starts picking up, and smoke starts settling on the lake. [Jess and Jamie] keep moving. The sky keeps getting darker, and they hear a roar in the distance.

They close campsite 7 quickly and paddle toward campsite 8, which is at the end of a long narrow bay at the southern edge of the lake. Jess has been uneasy with the thought of heading all the way in there and getting stuck. There’s probably nobody at that campsite. She’s concerned, but not too concerned: They’ll do site 8 real quick and then head north and break for lunch. That’s the plan. But soon as they reach the tip of the point to turn south, Jess decides “No this is not worth it. We need to get out of here.” (Pagami Report, p. 11)

That’s when Jess made the split second decision to paddle hard for the safety zone, instead of going in to campsite 8.

The choice to divert right at that moment was the first in a series of maneuvers that would ultimately lead to Jess and Jamie’s survival. Had she delayed this decision a few minutes longer (or even made a different decision), the entire day might have had a different outcome.2

So why did she pivot when she did?

Do you have any doubt it was because she had been thinking and talking about Saturday’s close calls?

Robin, Ryan And The Floatplane

Now we turn to the fourth canoe team. Monday morning, Robin and Ryan arrived to the lake while everything was still calm. Hours later, they were escaping to safety when a floatplane pilot dared to pick them up in the middle of a thrashing lake.

Their story also shows they learned from Saturday’s close calls. To see how they learned, let’s back up a bit. Per the report, here’s what their day looked like before things started getting DARC (Dynamic, Ambiguous, Risky, Complex):

[Monday] morning, Robin and Ryan attend briefing in ICP, then are flown in by floatplane. While in the air, Robin doesn’t see much fire activity, but he notices the fire has grown quite a bit since he left a couple days ago. They are dropped off around 1020, and meet Jess and Jamie at about 1045. The four of them talk about Saturday’s close call, divide up the day’s assignments, and then split up. The wind is starting to pick up, and smoke is starting to settle onto the lake as Robin and Ryan paddle several miles, closing campsites for about an hour. (Pagami Report, p. 10).

Did you catch it? Did you see how they learned? Jess and Jamie told them about the close calls.

Good thing they did.

Within a few hours Robin and Ryan were faced with some big decisions, and they made moves that ultimately led to their rescue and safety.

Putting It Together

In this post and the previous one, we looked at four different canoe teams, and how they learned from close calls two days earlier.

The two teams at the portage directly experienced Saturday’s close calls. What led to learning was the fact that they talked about their close calls.

Jess and Jamie did not experience the close calls themselves, but they heard first-hand accounts from two teams who were there, and then shared those stories with others.

Robin and Ryan learned because they heard the stories second-hand from Jess and Jamie.

You could disect the stories further, distinguishing different kinds of communication, different ways they learned, and different ways that communication led to learning.3 But instead let’s take a step back, and look at the pattern that runs through all these stories. There’s a profound truth that shows up again and again:

Communication is the key ingredient to Operational Learning.

This is another way communication led to learning. The obvious way is that Jess heard about Saturday’s close calls. The less obvious way is that she told another canoe team about them. I believe her act of telling (probably something more like “warning”) the other team is part of what primed her to make the decisions she did.

I call their day an “ONIMOD,” because was the opposite of a typical “domino” story where one thing goes wrong, leading to another and another.

For example, one way communication led to learning was that people recieved information they didn’t have. Another way it led to learning was that the act of talking about the close calls got them into a frame of mind and primed them to make the decisions they did.

Photo by Diego Catto, Unsplash